NASA

For the first time in a dog's age, NASA's human spaceflight program seems to be in a hurry. Although few in the aerospace industry expect the agency to meet its 2024 goal of landing humans on the South Pole of the Moon, this deadline has nonetheless spurred the space agency to move quickly with contracts on offer for a lunar space station, spacesuits, Moon cargo delivery, and more.

And then there is the space agency's grand prize. At the end of September, NASA asked industry to bid for large contracts—which eventually will be worth at least several billion dollars—to build a "human landing system" that will take astronauts from lunar orbit down to the Moon's surface. There is a lot to digest in these documents, which entail three-dozen attachments and several amendments. But now the time has nearly expired—the deadline for companies to respond is November 5.

These are hugely consequential contracts. If NASA's return to the Moon survives into future presidential administrations, the company that builds a human lunar lander will earn both prestige for landing astronauts on another world, but also potentially long-term contracts that may one day include landing humans on Mars.

But there are also risks. It takes huge amounts of time and money to respond to these solicitations. Moreover, companies will be evaluated, in part, on the extent to which they are willing to co-invest in their vehicle development. NASA wants to see skin in the game, which can be a risky proposition for a program that might one day be killed by the government. Finally, there is no guarantee these landers will ever be funded.

To specifically pay for lunar lander development in fiscal year 2020, which began on October 1, NASA has asked for $1 billion. The US House has yet to provide any lander funding with its budget for 2020, and the US Senate has provided $744.1 million. NASA presently is operating under a continuing resolution, which contains no funding for lunar landers. Given the contested political environment in Washington, DC, it is not clear when a budget for the current fiscal year will be approved or how much money will be appropriated for the lunar program.

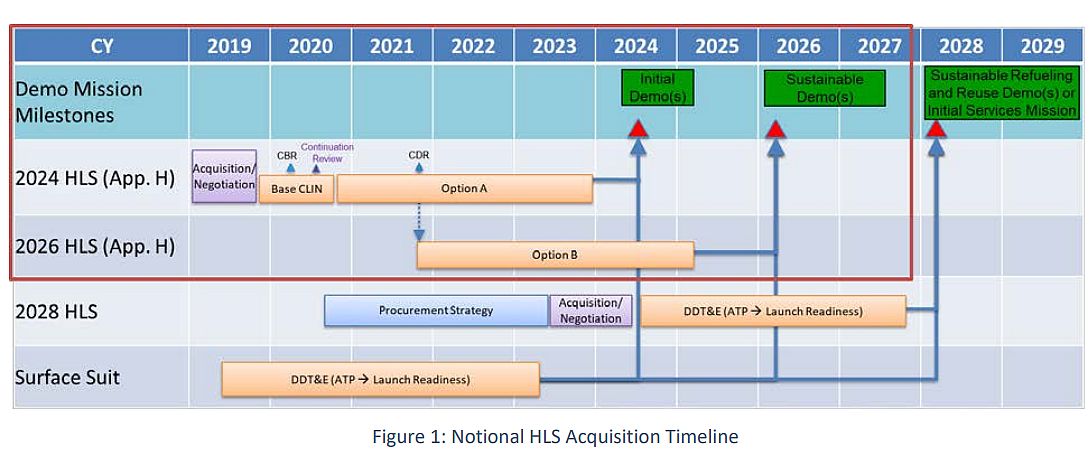

Space agency officials have said they would like to have multiple companies building separate landers, as they believe competition will provide incentive to meet the 2024 deadline and result in a better product. However, the number of providers will depend upon the amount of funding Congress appropriates. NASA has also said it would like to announce its lunar lander contractors in December, although one source told Ars this decision will likely slip into January. NASA hopes to award 10-month contracts to multiple providers for design and development in December 2019 (Base CLIN). After that, contracts for full development will follow to one (Option A) or two (Option B as well) providers. NASA

In any case, several teams of contractors are expected to bid for a pool of money that will start out in the hundreds of millions of dollars but may eventually grow to be worth much more than that.

This story attempts to assess the main contenders for this prize, some of which have publicly declared their intentions while others have not. This information has been gleaned from formal announcements, interviews, on-background discussions, and the companies included in earlier NASA awards to study human lander concepts.

Blue Origin

We know the most about Blue Origin's lander plan because the company's founder, Jeff Bezos, shared details of his blue-chip team at the International Astronautical Congress in October.

Blue Origin will serve as the prime contractor, building the Blue Moon lunar lander as the "descent element" of the system to carry the mission down to the lunar surface. Bezos' company will also lead program management, systems engineering, and safety and mission assurance. Lockheed Martin will develop a reusable "ascent element" and lead crewed flight operations. Northrop Grumman will build the "transfer element," and Draper will lead descent guidance and provide flight avionics.

An artist's concept of a BE-7 engine powering a Blue Moon descent module.

Blue Origin has proposed a "Blue Moon" lander to send cargo and potentially humans to the Moon.

Bezos said the lander could be used to carry humans down to the surface of the Moon.

Mark Wilson/Getty Images

The company plans had already hotfired the lander's engine, named BE-7.

Mark Wilson/Getty Images

Here's a diagram of the new BE-7 engine.

Blue Origin

This appears to be a calculated plan to win political support, as well as funding from NASA. The proposed three-part landing system fits nicely within the framework set by NASA and is sized to be launched on commercial rockets—likely United Launch Alliance's Vulcan booster and Blue Origin's New Glenn rocket.

Finally, this plan satisfies NASA's goal for company investment, as Blue Origin has already, with Bezos' funding, developed its own BE-7 rocket engine for the descent module.

Boeing

Boeing is assembling a team to develop a lunar lander for NASA, but a spokesperson for the company told Ars that Boeing does not plan to disclose any details until after November 5.

However, one source said Boeing will partner with Dynetics (an aerospace contractor in northern Alabama), Aerojet Rocketdyne (a major engine manufacturer), and Intuitive Machines (a company in Houston building a small lunar lander).

Intuitive Machines has previously been disclosed as a partner. Boeing selected Intuitive Machines to "build, test, and deliver prototype main stage and reaction control engines" as part of a precursor, technology development contract for a human lander system." Steve Altemus, the company's president and chief executive, said in an interview that Intuitive Machines has been test firing 3,500-pound-thrust main engines for a lunar lander, as well as developing avionics and storage tanks for cryogenic fuels. The company plans to ship the engines to Marshall Space Flight Center for further testing before the end of 2019.

Citing the competition blackout period, Altemus declined to discuss specifics of Boeing's proposal. But he said Intuitive Machines felt fortunate to be able to leverage the technology from its smaller Nova C lander, selected as part of NASA's Commercial Lunar Payload Services competition, to build something that will land humans on the Moon.

"I think the world of NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine and how he's pulling together this coalition to return humans to the Moon," Altemus said.

One big question is whether Boeing intends to build a lander in pieces—with transfer, descent, and ascent elements that will assembled at the Lunar Gateway—or as an integrated spacecraft on Earth that launches in one piece. Doug Cooke, a lobbyist for Boeing, has been writing op-eds suggesting the simplest and fastest way to return to the Moon involves such an integrated lander launching on an upgraded version of the Space Launch System rocket. This would seem to offer a powerful clue as to what architecture Boeing will propose.

SpaceX

SpaceX will be among the bidders for a human-lander contract, but the company has not offered details. "I don't want to talk about specific procurements, but we are aiming to be part of Artemis for sure," the company's president and chief operating officer, Gwynne Shotwell, said during an exchange with reporters at the International Astronautical Congress in October. "Falcon Heavy will be leveraged heavily in this adventure. Starship can be leveraged as well."

With a capacity of more than 15 tons to the Moon, the Falcon Heavy rocket is powerful enough to launch components of a lander to lunar orbit. But what's not clear is whether SpaceX has done any design work on elements (such as an ascent or descent lunar vehicle) that could fly on the Falcon Heavy. (If SpaceX has, we have seen or heard nothing of it). A prototype of SpaceX's Starship vehicle stands 50 meters tall in South Texas. Trevor Mahlmann for Ars

SpaceX may, instead, offer an integrated lander in the form of Starship. If fully realized, this combination of a large first-stage booster and uber-capable upper stage would more than meet NASA's needs to send humans to the Moon and back. Starship could also return, potentially, tons of Moon rocks.

However, SpaceX remains a ways from 1) building an orbital version of Starship—a test flight could come next year—and 2) from building life-support systems for humans on board Starship.

"Initially, we definitely want to focus on cargo," Shotwell said of Starship's development. "We want to make sure that design is reliable and that we've got a lot of time on it before we look at crew."

Knowing the preferences of SpaceX founder Elon Musk, he will want to press ahead full-steam on Starship development, which he views as the future of his company and the future of humanity's access to space. The question is whether NASA is willing to fund any of this development work for such a potentially revolutionary capability—SpaceX appears to be doing its part by investing heavily with its own funds in the Starship project.

Others

Other companies have been involved in NASA's earlier solicitation for ideas and technology needed for human lunar landers, such as Sierra Nevada Corp. (In a statement, the company said it "plans to continue to support NASA's Artemis program on future programs" such as the human landing system.) So there may be other bidders as part of NASA's competition. But for now, two sources said, the bids by Blue Origin, Boeing, and SpaceX appear to be the most serious contenders.